A satellite project of labs.iximiuz.com - an indie learning platform to master Linux, Containers, and Kubernetes the hands-on way 🚀

Container Tools, Tips, and Tricks - Issue #4

When Containers Are Not Enough

Believe it or not, containers are virtualization means. Even Linux containers that are “just isolated and restricted processes” can make a single server look like a hundred independent “machines” with their own network stacks and filesystems. And this is, by definition, virtualization.

Having a container per application is handy - you can choose a Linux flavor that suits your needs the best, install the application’s dependencies without fear of clashing with the neighbors, and enjoy the subsecond startup time, thanks to the “shared kernel” architecture.

However, sometimes, the virtualization provided by Linux containers may be too limiting. For instance, from time to time, I need to access Docker from within a container, but neither mounting the host’s docker.sock file into the container nor running Docker in Docker (aka dind) sounds good enough to me (because of security and performance implications). Another typical example is when extra boundaries (beyond namespaces, cgroups, and seccomp profiles) are required to protect the host from the workloads and the workloads from each other.

A solution that not only looks like providing a “machine” per application but truly creates these "machines" might be much more preferable in cases like the above.

Instead of relying on OS-level virtualization means, as Linux containers do, our ideal tool needs to be virtualizing the actual hardware where a separate Linux kernel (and maybe the rest of the operating system) can be booted. And that’s exactly what good old virtual machines do. But we got used to almost instant startup times of our containers, won't the virtual machines be too slow for us?

Turns out, some virtual machine monitors are faster than others!

Cracking VM performance

Firecracker looks like a good option if you need to run virtual machines that boot (almost) as fast as containers. The official starting guide is fairly straightforward, and Alex Ellis also made his own version of the starting guide showing additionally how to configure VM networking. Long story short, you need to get an uncompressed kernel binary and a (disk image of the) root filesystem, start the firecracker process, and point it to the said files using the HTTP API it exposes.

I was able to complete the guide from the first attempt without much trouble:

The feeling that I could have a bunch of Ubuntu (micro)VMs up and running in no time was just amazing. And at first sight, they even worked fine…

But then I tried running Docker inside one of the VMs, and it wouldn’t start. The pity is that I couldn’t even check the system’s compatibility because CONFIG_IKCONFIG wasn’t enabled in the sample kernel.

Apparently, the provided sample kernel binary is pretty old (4.14.x IIRC), and was compiled using a firecracker-optimized set of configs that are tailored for serverless workloads.

My first thought emotion was to figure out the right set of kernel configs myself. It turns out compiling a kernel is a simple task! Especially if you use a helper builder container:

# syntax=docker/dockerfile:1

FROM ubuntu:20.04 as builder

RUN <<EOF

set -eu

apt-get update

apt-get install -y bc bison build-essential \

ccache flex gcc-7 git kmod libelf-dev \

libncurses-dev libssl-dev wget ca-certificates

update-alternatives --install /usr/bin/gcc gcc /usr/bin/gcc-7 10

EOFFrom within the above container, you can build your own kernel with something like this:

git clone \

--depth 1 \

--branch v5.10.77 \

git://git.kernel.org/pub/scm/linux/kernel/git/stable/linux-stable.git \

linux

cd linux

# Copy your tweaked config to .config

make clean mrproper

make olddefconfig

# Build the kernel

make -j$(nproc)

# Your kernel is at ./vmlinuxBut even though the above snippet takes just a couple of minutes on my moderately performant server (Intel Core i7-8700 CPU @ 3.20GHz), my kernel knowledge (or rather lack of it) didn’t allow me to figure out the right set of configs within a reasonable number of attempts. And even if I would come up with a good enough kernel build, while simple, the original Firecracker UX is still pretty far away from the convenience of docker run.

Igniting microVMs with ease

Luckily, folks from Weaveworks have already figured everything out! The magical Weave Ignite project makes launching Firecracker microVMs as smooth as Docker containers.

Weave Ignite is a relatively thin wrapper (~20K lines of Go) around Firecracker that comes bundled with a set of precompiled kernels (at the time of writing this, the version list includes 4.14.x, 4.19.x, 5.4.x, 5.10.x, 5.14.x, and more) and root filesystems (Ubuntu 20.04, CentOS 8, Amazon Linux 2, K3s, etc). Kernels are based on the (already familiar to us) firecracker-optimized configs but with Weaveworks-authored patches applied on top to allow running tools like Docker and K3s inside of ignite-started microVMs.

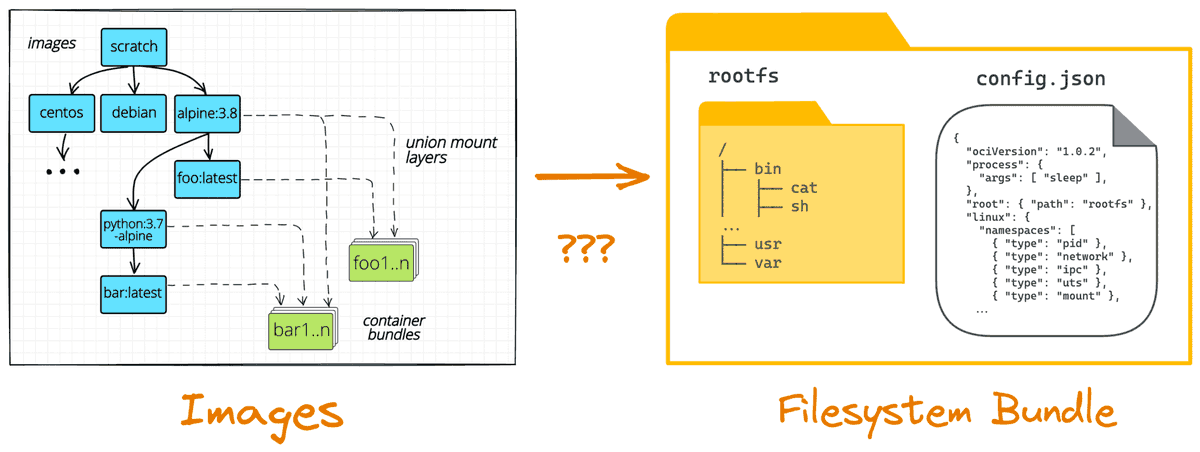

Both prebuilt kernels and root filesystems are conveniently packed as OCI images and stored on DockerHub (but you can build and import your own if you like).

Installation of the tool is relatively straightforward (using a bare-metal machine is a good idea but nested virtualization may also be an option):

- Ensure the dependencies (

apt-get install -y containerd dmsetup ...). - Download the CNI plugins.

- Download the

igniteand (optional)ignitedbinaries.

After you have ignite somewhere in your PATH, starting a microVM becomes as simple as:

# Pull in the right version of the kernel.

$ ignite kernel import weaveworks/ignite-kernel:5.10.77-amd64

# Pull in the rootfs of choice.

$ ignite image import weaveworks/ignite-k3s:latest

# Start the microVM.

$ ignite run weaveworks/ignite-k3s:latest \

--kernel-image weaveworks/ignite-kernel:5.10.77-amd64 \

--name my-vm \

--cpus 2 \

--memory 4GB \

--size 10GB \

--ssh \

--interactiveOne of the cool things about Ignite is how it leverages containers and the surrounding ecosystem. Not only rootfs and kernel images are stored and distributed as container images, but also containers themselves are used to run microVMs! For every ignite run (which is, much like docker run, just a shortcut for ignite create followed by ignite start), Ignite starts a sandbox Alpine container (using a local containerd daemon) that runs a special ignite-spawn binary. The ignite-spawn process serves as a launcher of the firecracker process that will represent the future VM (once it receives all the configs via the HTTP API it exposes).

Interesting that the firecracker jailer is not used by Ignite. The jailer is supposed to be restricting the firecracker processes even further by running it as a non-root user and using a tight seccomp profile. The ignite-spwan process seems to be running as root and in a quite privileged container (ctr -n firecracker c info ignite-081d6a7249aed6dc shows that CAP_SYS_ADMIN is used), so this design choice is rather questionable. Nevertheless, having a disposable container around the firecracker process is handy for garbage collection - no need to care about various filesystem and networking leftovers when the VM terminates.

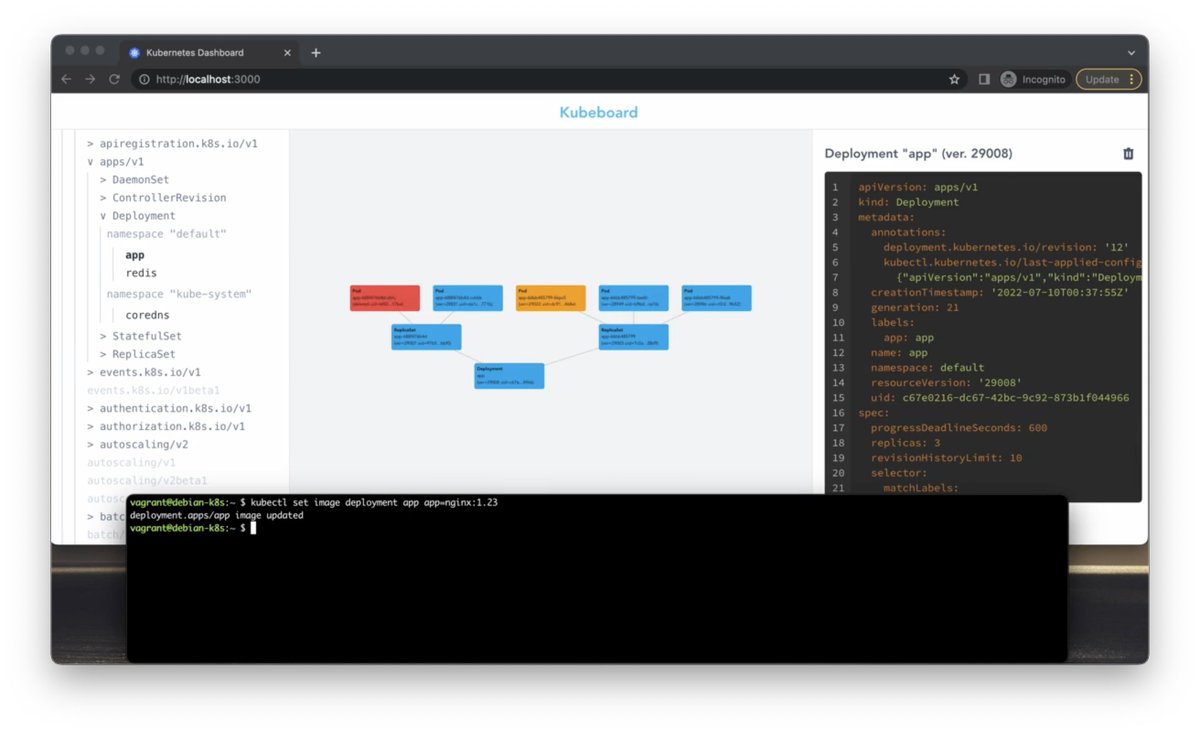

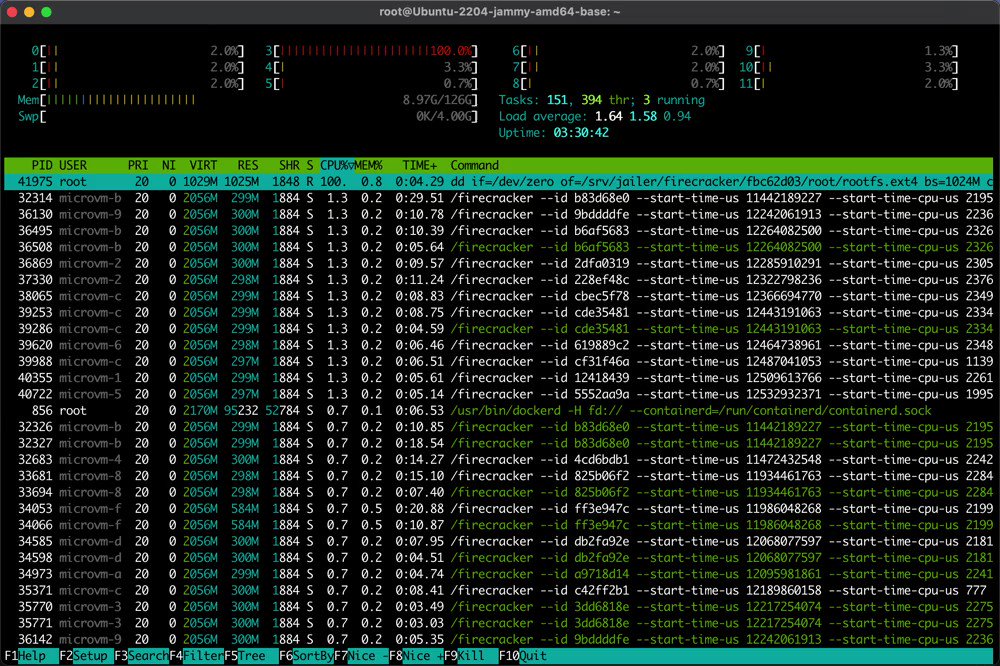

Here is what the process tree looks like on the host:

$ ps axfo pid,ppid,user,command

PID PPID USER COMMAND

...

238567 1 root /usr/bin/containerd-shim-runc-v2 -namespace firecracker -id ignite-03922f0748b8e931

238588 238567 root \_ /usr/local/bin/ignite-spawn --log-level=info 03922f0748b8e931

238674 238588 root \_ firecracker --api-sock /var/lib/firecracker/vm/03922f0748b8e931/firecracker.socUsing microVMs in the wild

Ok, it’s all fun, but you may rightfully ask, “What am I supposed to do with this knowledge?”

I’m a big fan of VM-based disposable and isolated dev environments and playgrounds. Traditionally, I’ve been using VirtualBox/Vagrant for that. But VirtualBox is pretty heavy-weight. It’s fine when it’s a longer-term project, but it creates friction for quick experimentation. With Ignite, though, you can get a full-blown VM in under a second (assuming the images have already been pulled), isn’t it just amazing? You can ssh into it, install every tool you need, break stuff as much as you want, and then just tear it down, leaving your host system clean and tidy.

Wanna keep it more boring real? You can use Ignite in your CI/CD to make it more reproducible and secure! Weaveworks folks claim it’s designed to be a “GitOps-first” project (remember this second ignited binary - it’s a reconciler).

And, of course, you can bake your own rootfs images containing all the tools you need - with Docker, it’s as simple as writing a Dockerfile and then building it to a folder using docker buildx build -o rootfs. Look how neat this Ignite’s Ubuntu + K3s example.

Fun fact: I wrote a blog post about this technique back in 2019 - little did I know that it’s used in the wild - the accompanying GitHub project even gained a few hundred stars since then.

Last but not least, even if Ignite is not directly suitable for your needs (it also looks a bit unmaintained at the moment), you still can learn from it! For instance, I use it as an inspiration and a source of ideas when I’m working on my learn-by-doing platform:

January 13th 2023

|

Ivan on the Server Side

A satellite project of labs.iximiuz.com - an indie learning platform to master Linux, Containers, and Kubernetes the hands-on way 🚀